Understanding the Importance of Context in Scientific Data

Written on

The Role of Context in Scientific Data

In today's world, we are inundated with an overwhelming amount of scientific information, charts, and statistics that could fill an entire library. Terms like “flatten the curve,” “the science is clear,” and “backed by scientific data” have become commonplace, akin to the overused phrase “at the end of the day.” But what do these concepts truly represent in our daily lives? Answering this question is anything but straightforward. Conflicting scientific perspectives can either guide us or lead to confusion. Much like the stock market, our minds tend to resist uncertainty; we prefer definitive answers, whether they are good or bad. However, the constant influx of contradictory information can lead to anxiety and inaction, not to mention the misinformation surrounding the coronavirus.

A few notable examples illustrate this point. For instance, the recommendation for washing hands for 20 seconds begs further inquiry. According to the CDC, evidence suggests that washing for 15 to 30 seconds removes more germs than shorter washes. However, after reviewing the provided references, it became clear that they primarily addressed bacterial levels rather than viral ones. Can we equate these two types of pathogens? Perhaps, but the evidence remains inconclusive.

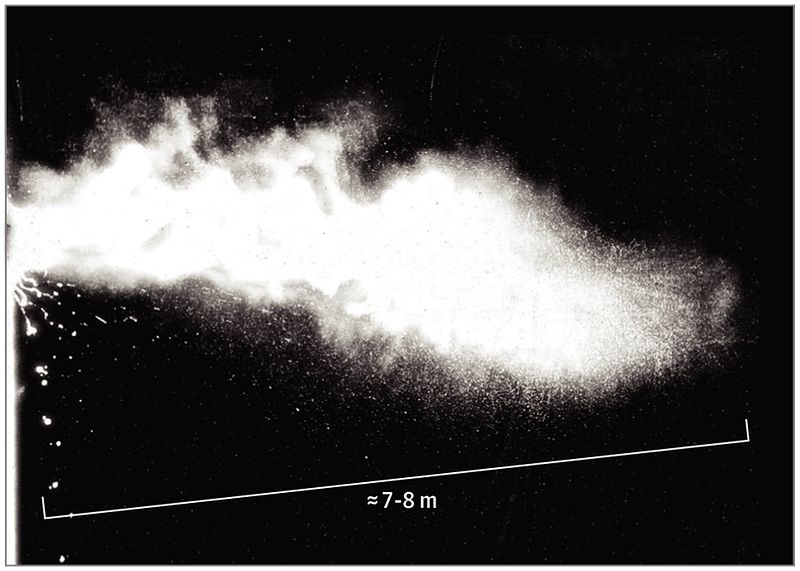

Further complicating matters is the guideline for maintaining at least six feet of distance for “social distancing.” The CDC recommends six feet, while the WHO suggests three, and a recent JAMA study posits a staggering 27 feet!

The foundation of this study revolves around how Covid-19 droplets are transmitted in turbulent gas clouds. So, which distance should we adhere to? Perhaps all three suggestions have merit, depending on context. For instance, in a poorly ventilated room, 27 feet may not suffice, while in a breezy outdoor setting, three feet might be more than adequate. The amount of virus expelled can also vary based on the activity—be it normal breathing, jogging, or sneezing. The duration of exposure also plays a crucial role. Hence, despite the proclamations of “experts,” the “science” is not as straightforward as it appears. Our approach to engaging with others must take into account our comfort with risk; younger individuals often feel invincible, while those who are older or immunocompromised may be far more cautious.

Consider the numerous studies investigating how long the virus can survive on various surfaces. Some suggest it lasts 24 hours on cardboard, while it can persist for up to three days on plastic and stainless steel, four days on wood, and five days on glass. However, these studies were conducted in controlled lab environments, which raises the question: can these findings be accurately applied to the cardboard box left on your doorstep? Likely not, which underscores how misleading headlines can be.

The misuse of scientific data is particularly evident in daily reports of case numbers and fatalities. While death is typically regarded as a definitive endpoint in medical studies, there is increasing debate over how accurately Covid-19-related deaths are classified. The existence of asymptomatic carriers complicates matters further, as increased testing will naturally lead to more identified cases. Does a rise in case numbers indicate that preventive measures are failing? Not necessarily; it could simply reflect expanded testing. Moreover, if 3,000 individuals succumbed to the virus today, it doesn’t automatically imply that the outbreak remains uncontrolled, especially if previous days saw higher death tolls. Understanding this virus requires time, a luxury we cannot afford as millions face unemployment and the urgent need to return to work.

Context is crucial. Data can be manipulated to reflect the biases of those presenting it, and while we might hope for objectivity from medical professionals, history shows this is not always the case. Science and medicine are powerful tools, but the rise of digital platforms allows anyone to claim expertise and disseminate information, often without peer review. A recent example includes a viral video featuring two ER doctors from Bakersfield, California, who downplay the necessity of lockdowns. In an age where anyone can broadcast their views, it’s imperative that we remain discerning about the information we consume and its motivations. As the saying goes, while you might “trust” scientific data, it's essential to also “verify” its validity.

If you found this discussion enlightening, feel free to follow me on Medium, Facebook, or Twitter @DavidMokotoff. Stay safe!