The Rise of Typhoid Mary: A Story of Networks and Disease Spread

Written on

Chapter 1: A Summer Dinner and an Unforeseen Outbreak

In the summer of 1906, the affluent Warren family gathered for a delightful dinner in their vacation home located in Oyster Bay, Long Island. The highlight of the meal was the refreshing dessert: Peach Melba served with ice cream, a favorite among the children.

However, just days later, one child fell ill with the symptoms of typhoid fever. Soon after, five others, including staff members, began to show similar signs. This was alarming, as typhoid fever was typically associated with unsanitary conditions, primarily affecting impoverished communities. The outbreak in this affluent setting was puzzling.

The concerned landlord, eager to maintain the reputation of his upscale rental property, contacted local health officials. They conducted thorough inspections of the premises, examining sanitation facilities and local food vendors, but all tests yielded inconclusive results.

Section 1.1: The Search for Answers

To solve the mystery, the investigator, Thompson, traveled to New York City in search of a specialist, whom he found in Dr. George Soper, a sanitary engineer rather than a medical doctor. After extensive research into the Warren family's circumstances, Soper noted a significant change: they had recently hired a new cook.

Upon interviewing the family, he learned that the cook's specialty was the very dish that had caused illness—Peach Melba. This raised his suspicions, as cold dishes are known to harbor live bacteria more than cooked meals.

Subsection 1.1.1: The Hunt for Mary Mallon

The cook, Mary Mallon, an Irish immigrant, had vanished shortly after the outbreak. Soper dedicated months to tracing Mallon’s history and discovered a disturbing pattern: she had previously worked for seven other families, each experiencing typhoid fever outbreaks, collectively infecting twenty-two individuals. If Mallon was indeed a healthy carrier of the disease, locating her was crucial.

By March 1907, Soper successfully tracked down Mary Mallon, later dubbed "Typhoid Mary" in the media. Confirmed as a healthy carrier of the typhoid bacillus, she spent the next three decades in isolation, occasionally escaping to cook again but ultimately facing re-arrest and quarantine. She passed away in 1938 from pneumonia, never having displayed symptoms of the disease herself. However, an autopsy revealed significant levels of the bacillus in her gallbladder.

Chapter 2: Understanding Disease Transmission through Networks

In Soper's pioneering work, he marked a shift in understanding disease propagation. Prior studies had focused on geographical locations, such as the Broad Street cholera outbreak in London in the 1850s. Soper's approach was groundbreaking as it tracked disease spread through individuals rather than places, laying the foundation for modern insights into how information flows through social networks.

The way information travels through networks parallels disease transmission. Hence, the term "viral" is often used to describe rapid information spread today. This early research also informs our understanding of how trends and rumors circulate in contemporary society.

Section 2.1: The Dynamics of Information Flow

In its simplest form, the flow of information between individuals relies on two critical factors: the number of connections a person has (denoted as k) and the probability that the information will be shared (denoted as p). In Mallon’s case, influencing p proved challenging due to her entrenched hygiene habits. Thus, reducing k by isolating her was the most viable strategy to contain the outbreak.

In social networks, manipulating p and k is essential for managing the spread of marketing, news, or misinformation. Increasing p can be achieved by ensuring the topic resonates with the individual's interests or by establishing a clear agreement for sharing the information. Conversely, k can be expanded by engaging with influential individuals within the network.

Section 2.2: The Complexity of Rumors and Trends

The model of p and k oversimplifies the intricate dynamics of how trends and rumors spread across networks. The transmission of information depends on both the willingness to share it and the desire to receive it. Additionally, social networks often feature complex interactions where information can circulate in various directions.

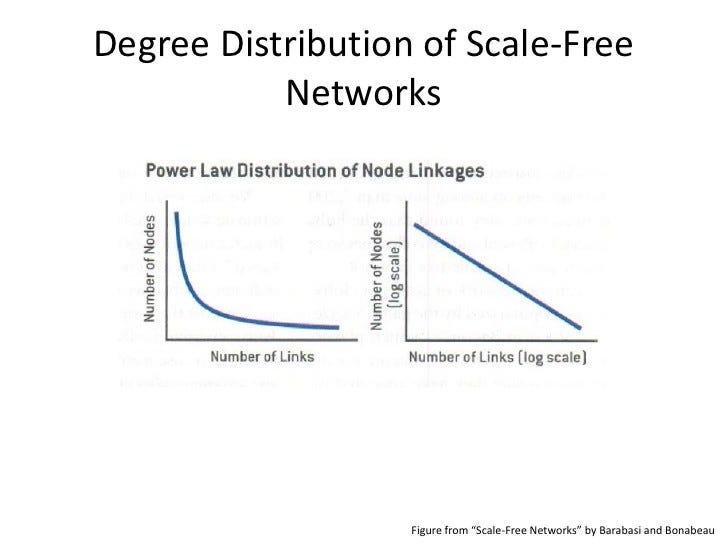

Recent studies on rumor propagation within social networks reveal fascinating insights. Platforms like Facebook and Twitter display characteristics of scale-free networks, where a small number of individuals hold numerous connections while many others have few. This structure allows information to spread rapidly, with Twitter, for instance, enabling a single piece of information to reach approximately 50 million users within just eight exchanges.

Chapter 3: Predicting Trends in Social Media

When browsing social media, you often encounter trending topics. Social media platforms leverage the principles of information propagation to develop algorithms that identify when a topic gains momentum within their networks.

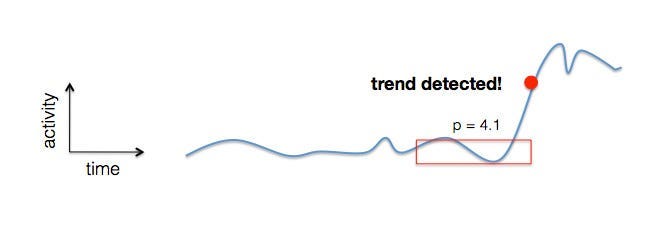

Basic trend models track specific topics or tags over a defined statistical period. This monitoring reveals spikes in activity that indicate a topic's potential to trend. However, relying solely on this method can lead to inaccuracies and necessitates human judgment, which is impractical in vast networks.

In a significant 2012 MIT study, researchers devised a fully automated approach to predict Twitter trends with a 95% accuracy rate, using historical data to identify patterns in tweeting activity. This innovation laid the groundwork for the trend prediction methods widely adopted by social networks today.

For a deeper dive into these themes, consider referring to my textbook on Network Analysis.